A foodie. An avid reader. A huge Disney fan.

These are things you might not know about Drs. Joseph Chattahi, Sharon Deskins and John Schuen. They are all amazing doctors, but behind their credentials, they're loving family members, community members and more.

This year leading up to Doctors' Day on March 30, we're focusing on “Celebrating our shared humanity.” We're learning and sharing more about our doctors outside of work — what they're passionate about, their hobbies and the things that join us together. Learn more about three of our doctors below and join us in thanking them, and all our doctors, for the passion and dedication they pour into their profession.

Read more doctors' stories on our Doctors' Day Well page.

Dr. Joseph Chattahi on the ‘human part of being the doctor’

The patient was dead for an hour and 15 minutes. There was less than a 1% chance he could come back, said Joseph Chattahi, M.D.

But his team didn’t give up. For that entire hour and 15 minutes, they actively performed CPR to save the 39-year-old man, and their efforts were successful. Now, every time the patient sees Dr. Chattahi, he gives him a big hug.

“Every person in their career comes across one thing that's going to always stick out in their memory, and they never forget it,” Dr. Chattahi said. “When they come back to the clinic, and they give you that hug and tell you ‘Hey, you saved my life,’ that's what makes it all worth it.”

Dr. Chattahi is chief of internal medicine at Corewell Health Taylor Hospital and director of Corewell Health Dearborn Hospital’s structural heart disease program. Specializing in cardiology, he has performed rare valve-in-valve procedures and helped pioneer an oxygen therapy to heal hearts damaged by once unsurviveable heart attacks.

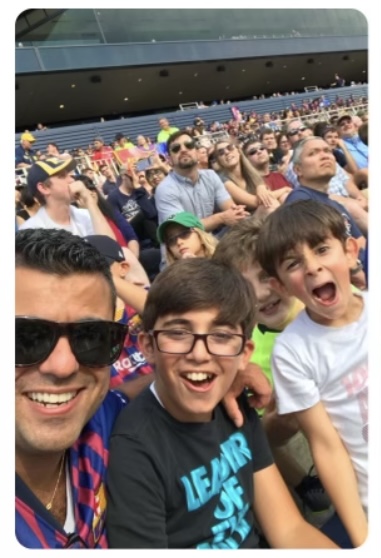

When he’s not saving lives, he can be found traveling to Malaysia, Thailand, Egypt, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Brazil, Mexico and more for both vacation and humanitarian missions. He’s a big foodie, especially whole fish dinners or steak (“not the best for a cardiologist,” he joked) or enjoying soccer with his three sons. Everybody has a different favorite team, but Dr. Chattahi supports Barcelona.

Being a doctor was his childhood dream. He didn’t have any physicians in his family, though they were certainly thrilled by his career choice. He wanted to be like the doctors on the medical shows he watched. He wanted to be the person in the restaurant who answered the call when someone was choking, he said.

He’s been practicing medicine for close to 20 years, and he’s come to understand that serving and saving patients is a team effort. It’s not just the doctors, but also the nurses and the administration team. Everybody has their role, and when you put all the pieces together, “you get success,” he said.

He’s also realized the importance of the “human part of being the doctor.”

Doctors aren’t working with objects, but human beings. If a doctor is having a bad day, they can’t just “bail” on the 20 patients in the waiting room and take the day off, he said.

When patients are sick, they’re vulnerable and weak. They need comfort, support, and someone to walk them through what’s happening, even when it’s hard, Dr. Chattahi said.

He puts himself in their loved ones’ shoes. Like the 39-year-old patient his team saved. How long was long enough to keep trying to bring him back? Dr. Chattahi said if he was the patient’s family member, he would have wanted them to keep going, so they did.

“Once we lose that connection, then we fail in our jobs,” he said.

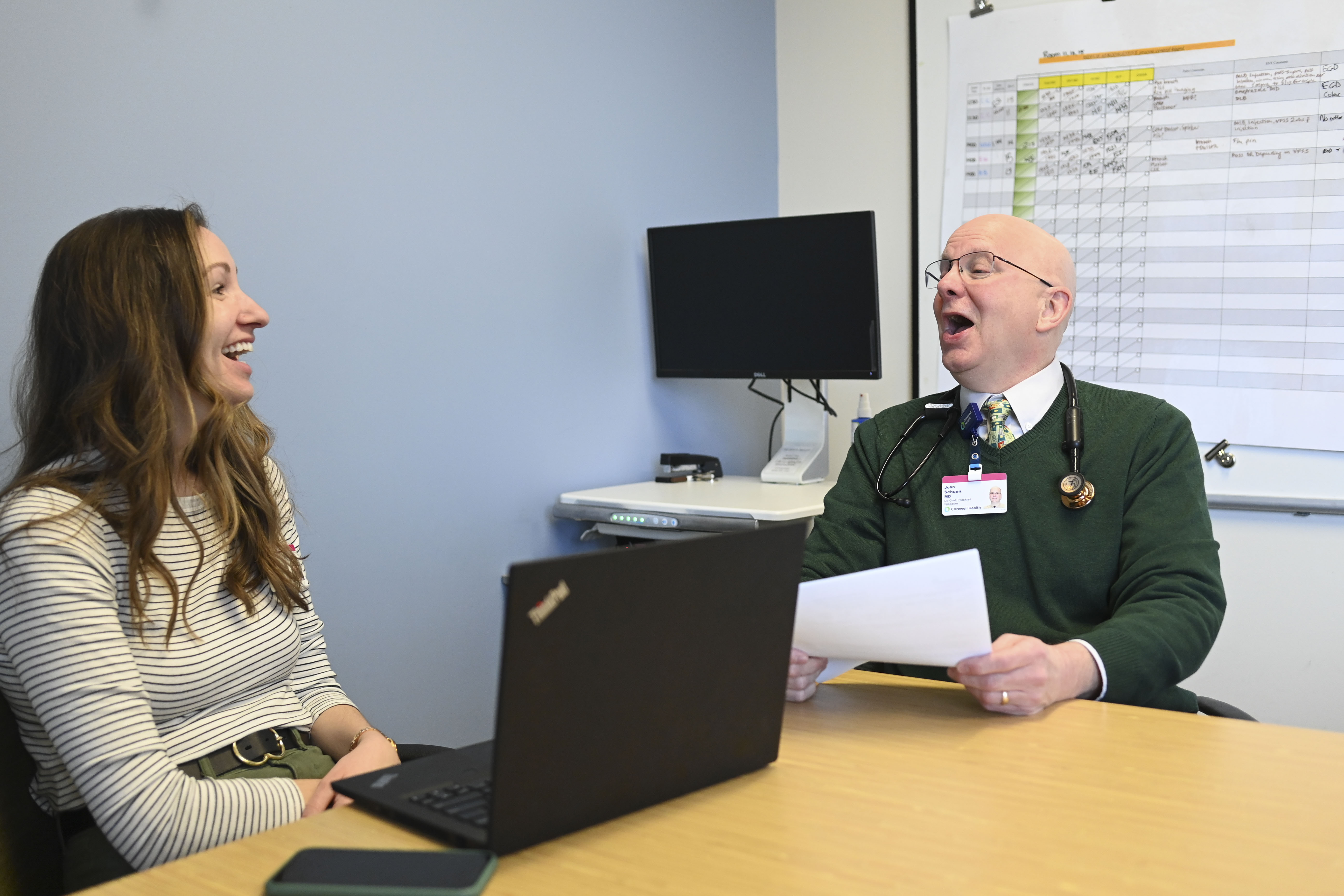

Dr. Sharon Deskins on the power of storytelling and connection

Something that connects us all — whether you’re a doctor, a nurse, a patient or simply, a human being — is our need to be storytellers, said Sharon Deskins, M.D.

“We tell stories all the time,” she said. “Stories about ourselves, stories about others; it influences who we are and how we interact with the world. Stories are everywhere.”

Dr. Deskins’ story includes growing up in Ann Arbor, where she attended the University of Michigan Medical School. She then moved to California, where she did her residency and internship at the now named Los Angeles General Medical Center.

She lived in California for 10 years but knew she wanted to come back to Michigan to raise her four kids. She’s been back in the St. Joseph area practicing medicine for about 30 years.

What Dr. Deskins likes about medicine is how it combines several of her passions. She’s always been interested in science and trying to make peoples’ lives better. And she loves learning, which there’s certainly no shortage of in medicine.

“It's something that's never going to be boring. It won't be, after about five years, ‘oh I've mastered everything,’” she said. “There’s always something new to learn.”

And then, of course, you meet so many different people in medicine. Like Dr. Deskins’ almost 101-year-old patient who served in the Navy during World War II and is part of a book club. Dr. Deskins is also an avid reader, reading about 120 books a year.

Patients aren’t always clear medical storytellers. They might give unnecessary information or be sporadic with timelines. That’s why you listen — so you can pick out the important information for their medical story, Dr. Deskins said.

Dr. Deskins also works closely with Corewell Health South internal medicine residents and Michigan State University and Central Michigan University medical students.

Just like with her patients, Dr. Deskins talks to the residents to find out what they’re interested in. What are their life goals? What makes them feel loved, involved, respected?

“People are similar in a lot of ways. We all want connection, validation and love, though we may want them in different ways,” she said. “It should be fairly easy to make connections if you just take a moment, show some curiosity and ask people questions."

“You'll be surprised what you find out.”

Dr. John Schuen shares the ‘joyful practice’ of pediatrics

Even from his residency days at the Cleveland Clinic, John Schuen, M.D., was meant to work in pediatrics.

During his clinical rotations, there was a noticeable difference in his demeanor: Working in pediatrics, Dr. Schuen was happy and energized. So much so his wife knew he must be working with kids without him even telling her the month’s rotation.

“When kids are suffering, it's hard,” Dr. Schuen said. “But I think the desire to alleviate suffering, and to see them on the healthier side, brings tremendous joy.”

Today, Dr. Schuen is the division chief of pediatric aerodigestive specialties and a pediatric pulmonary/sleep medicine physician at Corewell Health Grand Rapids Hospitals - Helen DeVos Children's Hospital. The self-proclaimed huge Disney fan has been with the hospital since 1996 and working there has brought him great satisfaction over the decades.

He also recently served as chair of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s Center Committee, which oversees clinical guidelines and policies for cystic fibrosis care centers throughout the U.S. In that role, he traveled all over the country, visiting different sites and mentoring center directors.

Growing up, his career mentors were his dad, uncle, mother and grandfather, who all worked in medicine or dentistry. They all had a passion for taking care of people and wanted to make the world a better place. Something Dr. Schuen shares.

"I'm happy to see people thrive and get better,” he said.

He takes care of children with asthma, cystic fibrosis, sleep apnea and more, helping them get their condition under control so they can live their best life and experience life to the fullest.

Depending on their age, he has a specific approach with his patients. With a 6-month-old baby, for example, he gets to enjoy their interaction with their family in the moment. But when a patient is older, he wants them to tell their story as much as they can. A 4-year-old can often articulate that their chest hurts, they can’t breathe and express the need for help.

One of the challenges with children is helping them to understand their disease at an age-appropriate level. In this way, the patient and their parent will know “the why” and “what’s in it for them.” So, when they have to take “yucky prednisone” for a few days or daily inhaled steroids for months or even years, they understand that this will help them feel better, keep them out of the emergency room or avoid admission to the hospital.

It’s important to switch from speaking “doctor-ese” and other five-syllable medical jargon he uses with his colleagues to something that will make sense to the child, and in turn their parents, he said.

“Their parents have to be their advocates, and we have to be their advocates,” Dr. Schuen said. “The kids need all of us working together to help them help themselves.”